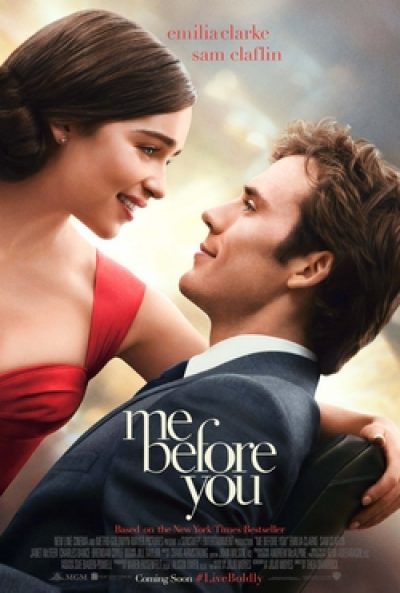

Me Before You (Ros' Blog)

There are many things that Christians may disagree about, some of them peripheral and others perhaps more foundational. But one thing I think all of us can agree on is that the Bible gives a clear picture of every human being as made in the image of God and being of infinite value because of being chosen, created and loved by God. As a result, no life is insignificant, and every human being matters to the moment when they draw their last breath.

I am thinking about this at present because I have just come back from seeing Me Before You, and honestly, it is hard to know where to start analysing all that is wrong with this film. It typifies the anxiety of the 'worried well' that disability must be unendurable – something most disabled people would strongly disagree with. The story is of Will, a young man paralysed in a road accident, who falls in love with his carer/companion, Louise, but nevertheless opts for suicide, handily leaving her a small fortune.

Perhaps one of the best ways I can convey this is to ask you to imagine a film in which a black person living in a largely white community (and played by a white actor 'blacking up') concludes that his life is so unlike that of the white people around him that he would be better off dead, and obligingly commits suicide, leaving a large amount of money to someone who is thus conveniently enabled to leave a life of poverty and restriction in order to better herself. Of course Hollywood would never make such a film – there would be outrage at such dehumanising and belittling of someone for their ethnicity, and quite rightly too.

But apparently Hollywood has no such qualms about a non-disabled actor 'cripping up' to tell us that if you lose the physical abilities you once had, nothing – not even the vibrant and devoted love of a person full of life and zest – can ever make your life worth living again. While this is not seen as acceptable based on ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation or any other trait, disability is placed into another category and it is apparently tolerable to diminish the value of disabled people’s lives to the point where they should consider themselves better off dead.

Why, in the twenty-first century, is such an idea even countenanced? The messages of this film seem to be:

- If your current boyfriend is enough of a selfish pig you might even fall for a cripple

- Even the strongest of human spirits is not indomitable enough to weather a terrible storm and wait for life to feel better again

- Needing assistance with bodily functions robs you of all your human dignity and leaves you with no hope but to find 'dignity in dying'

And that’s the key to the message of this film. There is a highly lucrative business in persuading people to believe that assisted dying affords more dignity than assisted living. Of course it is far cheaper for health insurers in the US and the NHS in the UK to kill someone than to provide for their lifelong care. But is that any reason to keep pushing this message into the public consciousness? The teaching of the Bible and the example of Jesus tell us that no price is too great to put on a human life.

But there is a money-making racket around the euthanasia industry; it is scandalous, but a lot of money is being made by persuading people that they are a burden and that they have no future. This film draws a veil over the realities of assisted dying. It does not show the moment of administration of the lethal dose, nor of Will’s death. There may be good reason for this – statistics show that 23% of assisted suicides and 9% of cases of euthanasia experience complications including failure to die, failure to induce coma, waking up after coma or taking longer than expected to die. One study in the Netherlands, where assisted suicide and euthanasia are legal, showed that 18% of assisted suicides turn into euthanasia cases because the patient fails to die and the doctor has to administer a lethal injection.

No doubt this is in part why, as I am writing, it has just been announced that 63% of doctors in the UK have voted against a motion for the BMA to abandon its traditional opposition to assisted dying. The Netherlands is a salutary example, because increasingly, its elderly patients have had to take to wearing badges saying, 'Doctor, please don’t kill me.' Even here in the UK, I am regularly asked if I would like 'Do Not Resuscitate' written on my healthy, young, disabled daughter’s medical notes, something no one ever asks about her non-disabled sisters. (If you haven’t already signed my petition against this, you can do so here.)

I am not seeking to diminish the intense grief of someone who has led an active life and suddenly becomes disabled. And I know at first hand the grief of a parent whose child becomes disabled – enormous enough when it happens, as in my daughter’s case, at only 9 weeks old, and probably heightened all the more when the child has led an active, athletic life before becoming disabled. But that is only the beginning of a long story, and this film tries to make it the end.

When I was a teacher euthanasia was one of the topics I had to teach. I used to show my classes a Channel 4 documentary about the battle of Diane Pretty to have a suicide lawfully assisted by her husband – a battle which went all the way to the European Court of Human Rights and was defeated at every stage by wise judges who could see, far more than this poor woman who was being manipulated by a pro-euthanasia organisation for its own ends, the far-reaching, unintended consequences that such a ruling would have.

I used to point out to my classes the many fallacies in the documentary – for example, when the care staff performed for the camera a soiled pad change and the narrator explained how terrible it was to have lost all human dignity in this way, I explained to my students that for many years I’ve had carers coming in to assist with this task for someone I care for, and we all make light of it and carry it out with cheerfulness and humour. The sense of loss of dignity is not a fact but an attitude, and one that, in Diane Pretty’s case, was being stoked up to the maximum by a disingenuous organisation campaigning for euthanasia. Shockingly, her mother said, “If it was an animal, you would have it put down” – but the point was that Diane Pretty was not an animal but a precious human being whose life was greatly enriched by the faithful love of a devoted husband and family.

Some things in the film Me Before You are just plain silly – when Louise peels back Will’s bed sheets, it reveals an improbably muscular torso and arms for someone who has been a quadriplegic for two years. Miraculously, Will’s bodily functions suspend themselves unless his male carer is present, so the love of his life never has to deal with a bag of urine or a soiled pad. And, having repeatedly nursed my own quadriparetic daughter through many a bout of pneumonia, to see him lying in hospital, at death’s door from pneumonia, his skin a rudely healthy pink, made me want to laugh out loud, and underlined the fact that this is a film made by non-disabled people, for non-disabled people, both of whom have no idea of the real magnitude of the problems presented by severe disability, nor of the heights of triumph of which the human spirit is capable.

As Christians we have to counter this terrible message that disabled lives are disposable. We have to affirm to our disabled friends and loved ones that their lives are significant, worthwhile and treasured. And perhaps we should be pointing out to friends who go to see this film that if someone is suicidal, he isn’t suffering from disability, he’s suffering from depression, and the solution is not to kill him, but to treat his mental health.

If you want to see an antidote to the terrible message of this film, why not take a look at Through the Roof’s video See The Possibility, and if you like its message, you could share it via social media so people can see that Me Before You doesn’t have the last word.

(Image is the theatrical release poster for the movie)